|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

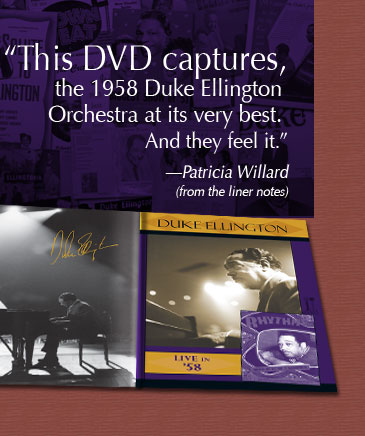

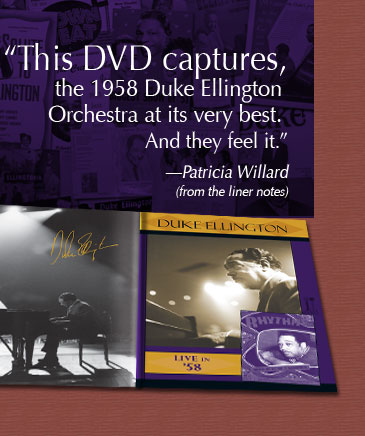

Jazz Icons: Duke Ellington features the earliest-known filmed full-length concert by one of the 20th Century's greatest songwriters and bandleaders. Filmed at Amsterdam's famed Concertgebouw, this 80-minute concert features the 16-piece Duke Ellington Orchestra two years after their stunning performance at the 1956 Newport Jazz Festival,which Duke considered his second birth. This epic performance includes legendary players Clark Terry, Johnny Hodges, Harry Carney, Paul Gonsalves, Quentin Jackson and Ray Nance performing some of the most beloved American music ever written. |

|

|

|

|

Reeds: Johnny Hodges (Alto Sax Russell Procope (Alto Sax, Clarinet) Paul Gonsalves (Tenor Sax) Jimmy Hamilton (Tenor Sax, Clarinet) Harry Carney (Baritone Sax, Clarinet, Bass Clarinet) Trumpets: Trombones: Rhythm section: |

|

|

|

|

|

Foreword: My name is Edward Kennedy Ellington II, and Duke Ellington is my grandfather. So much for all my positive qualities. During my life, there have been numerous attempts, by friends and family, to show me the proper path. Unfortunately, their noble endeavors have rendered mixed results. Two lessons by my grandfather come to mind. Once, while performing at the Rainbow Room in Manhattan, Ellington discovered the band lacked one musician for the union mandate. He immediately told me to borrow one of my father Mercer’s trumpets and sit next to Cootie Williams in the trumpet section. The euphoria of actually being in the Duke Ellington Band was so overwhelming that I began to believe I could actually play. As I raised the trumpet to my lips, Cootie said, “If you play one note, you’ll be dead before it’s heard.” —Edward K. Ellington II

Sample Liner Notes by Patricia Willard: Duke Ellington and his orchestra were enjoying heady years after their triumph at the 1956 Newport Jazz Festival where Paul Gonsalves’ electrifying midnight performance of “Diminuendo In Blue and Crescendo In Blue” moved the audience to turn the aisles of Freebody Park into an alfresco dance floor. Steadfastly focused on the future, Ellington declined requests thereafter to discuss his earlier career with, “Let’s not get historical. I was born at Newport in 1956.” ... The only two days the musicians were not onstage were devoted to interviews updating the press on the intervening years and promoting the remaining performances. Media coverage was intense. Some critics wanted more of the classic Ellington they had enjoyed a quarter-century earlier, and some felt deserving of an all-new program, composed exclusively for the tour. Max Jones, in The Melody Maker, complained, “They got something to please everybody, and were delighted…but not left limp,” concluding, however, that “Ellington still leads the world’s richest, most rewarding jazz band.” Duke was in high spirits. Their Atlantic crossing on the Ile de France had been privileged, he reported, because “Norman treats artists with such respect and indulgence. He makes you feel that you are ensconced upon an enormous satin pillow while your every wish is being granted.” Most impressive to the bandleader was his being presented to Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II at the First Leeds Festival of the Arts, on Saturday, October 18. Ellington, who took the nickname given to him by childhood friends seriously, spent a lifetime living up to his dubiously acquired title. “She told me she was sorry she couldn’t see the concert herself,” Ellington reported. “I told Her Majesty that meeting her made me feel tremendously inspired, and that I must write something to mark the occasion.” Four months later in New York, Duke conducted the first of several recording sessions for “The Queen’s Suite”. Much was made of his announcement that only one copy [LP] would be pressed, and that it would be dispatched by courier to Queen Elizabeth. While the band played individual pieces from this collection in concert, not until 1976 were rights negotiated with the Ellington Estate for a recording of the entire suite to be distributed to the public. With a day set aside for Channel crossing, the performance barrage resumed on October 28. Now under the exclusive aegis of Granz, they were booked again with double concerts at nearly every venue, beginning with the Palais de Chaillot in Paris and on to Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Austria, Switzerland, Italy, and culminating at a third Paris site, the famed Salle Pleyel on November 20. “We talked about being exhausted…from a major concert every night in a different city or country,” remembers valve trombonist John Sanders, now Monsignor Sanders, “but once you got your instrument out and your uniform on, all the rigors of travel disappeared. We could feel the music speak to the people. It was an exciting experience.” ... Ellington was an original. The musicians he collected were originals. He orchestrated them in opposition and apposition, defying tradition (“Rules are made to be broken,” he decreed) but acquiescing to superstition, hearing music in a palette of colors and conceiving chords, which sometimes could not be captured on manuscript paper, to produce some of the most tantalizing harmonies and agreeable dissonances ever heard. Succeeding generations read scores and parts in his archives but no one can make them sound like Ellington’s musicians because this music was organically theirs, written for their unparalleled talents, peculiarities and limitations. The Maestro never sought formally schooled sidemen. More often he searched for unique personalities. Experience was both an advantage and a detriment. With Jackson and Procope, theirs was profound seasoning, and with the fresh, adolescent Carney, unnecessary. Within months, Harry decided to explore the deeper baritone sax “because it seemed like the man of the saxophone family.” ... Growling through a mute was new to Nance. He promptly became the devoted disciple and running buddy of mute specialist, trombonist Joe “Tricky Sam” Nanton. “It wasn’t easy…apart from the pressure, you’re blowing with one hand and manipulating the mute with the other,” Ray explained. “It isn’t just a matter of blowing with the mute in there either. You’ve got to concentrate to produce a certain kind of sound, and you’ve got to want to do it. I like it because it has great descriptive quality.” Twenty years later, Ray switched to cornet because “it has a warmer tone than the trumpet, and because it’s shorter. Since I use the plunger so much and my arms are not long (Nance was five feet, four inches tall), it is more comfortable for me. And, too, I play the lower parts in the section, and it’s a better blend between the trumpets and the trombones.” ... Alto saxophonist Johnny Hodges, undoubtedly the most in-demand soloist in the band, looks nonchalant but plays with restrained eloquence and stirring intensity in Gerald Marks and Seymour Simons’s “All of Me”—the only other non-Ellington number on the concert. In the band’s book since 1949, this appealing standard evolved into a popular vehicle for Hodges in 1957. “Things Ain’t What They Used To Be” (originally titled “Time’s A’Wastin’”) became the rollicking Hodges encore everyone anticipated early on and couldn’t help but move their feet to. Hodges came to Ellington in 1928 on recommendation of bandleader Chick Webb and Carney, Johnny’s childhood friend. The pair lived in neighboring Massachusetts cities—Cambridge and Boston—and would explore tonal qualities and harmonic concepts together at Carney’s Boston home. ... Paul Gonsalves believed that music was the most profound statement of beauty. He loved ballads but he was always up for anything Ellington or Strayhorn, even if audiences expected to relive Newport ’56 every time he played what Duke had come to call the “whaling” interval in “Diminuendo in Blue and Crescendo in Blue”. Here, amazingly, he does it again with the driving support of the same rhythm section of Woode, Woodyard and Duke and finger-snapping, handclapping brass and reed players. Trumpeter William “Cat” Anderson ascends climactically to the spectacular “Crescendo”. This DVD captures the 1958 Duke Ellington Orchestra at its very best. And they feel it. See the musicians’ smiles. Ray Nance’s ecstatic expression with his violin, as he dances. “Butter” smiling every time he lifts his horn. Carney exuberant in his chair. Woodyard grinning at his drums. Except for the dour Hodges? No. After the DVD credits finish, we get to watch the band pack up and disperse. Look carefully—before he leaves the stage, the camera catches Johnny Hodges smiling! —Patricia Willard All words and artwork on this page ©Reelin' In The Years Productions. Unauthorized use is prohibited.

|

|

Site contents ©Copyright 2007 Reelin' In The Years Productions

Site designed by Tom Gulotta